Talk Max and Lea

Max Wallenhorst and Lea Langenfelder

Max: Dear Lea, my notes are as sketchy as a Pseudo-Focauldian take on hygiene around 1900! That means: I’m ready to come clean with you – to talk about what we saw and thought at the second edition of Dirty Debüt under the title of clean! Clearly, I’m also very ready to not clean out every single related / unrelated pun...

Talk Max and Lea

Max Wallenhorst and Lea Langenfelder

Max: Dear Lea, my notes are as sketchy as a Pseudo-Focauldian take on hygiene around 1900! That means: I’m ready to come clean with you – to talk about what we saw and thought at the second edition of Dirty Debüt under the title of clean! Clearly, I’m also very ready to not clean out every single related / unrelated pun.

Clean, I feel, is a dirty word – at least in my life of being around people who make performance. Some of them clearly see clean qualities as a counterproductive disinfectant to the milieu of transgression surrounding the historical trajectory of performance. (A tradition, that was so present in the first urine-themed edition of Dirty Debüt.) I think a lot of people rather want their work to be seen as dirty, as exactly the right kind of dirty. They only use an idea of clean aesthetics in a critical way when they try to mock “neoliberalism”. On the other hand – though not talked about much – a certain degree of cleanliness is obviously a requirement for the working conditions performance-makers find themselves in. In a precarious and international field their work needs to travel – across genre-boundaries and national borders. And that flexibility sometimes seems a lot easier if the work takes a clean shape. While most the of the work that was presented to us that Friday evening engaged with clean on a level of content as well, it was I think this ambiguity that was in the background of my experience that night.

Lea: Max, I just started my washing machine to remove the mustard stains on the black pullover you handed me back before the show! While listening to the sound of the seemingly endless turning machine, I’m thinking about your definition of “clean” as a dirty word. For me, too, it’s a pretty ambivalent term, which becomes clear, especially within the act of cleaning, which describes the process of gaining inner and outer space. It aims to obtain a clear view on the one hand, but on the other hand also some kind of interruption. An interruption or change in a relationship between people or in the relation to oneself, cleaning often appears to be connected to a stage of transition.

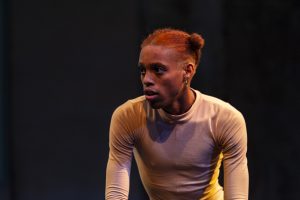

Yesterday, after having seen the four pieces, I googled “clean bodies” and “dirty bodies”. The first eye-catching content I found among pictures of people playing in mud was a book of the scientology founder Hubbard, concerning detoxification, blogs about self-optimization and some racist comments and pictures. “Clean”, when it comes to the body, for example the body of a performer, of course turns out to be a strong ideological term. And at least on some level, all of the pieces we saw at the second edition of Dirty Debüt were concerned with body politics. In particular, I strongly remember Jupiter Brown’s performance “bathwater”, the last performance of the evening.

I witnessed a performer dissolving meaning levels of a Black queer body, tracing this bodies’ history, the past of his cells. Do you remember your DNA, the underlying poem sound file was asking us, as Jupiter Brown was dancing, pausing, dancing again in front of a video projection of water, then bacteria, then water again. Supported through the use of these large array of mediums, not only was the performer’s body presented as an ephemeral construct, but the whole presentation itself. Jupiter Brown unmasked the concept of a “clean” shape of a human’s body as an absurd attempt of simplifying categorization. Between an improvised pose and a fluid grin, Brown played with the spectator’s desire for clearness and never satisfied their wish for stagnancy: Excessive demands as a method of performing. Brown’s very own shape was consulted in such a playful, inexorable and ironic way, not stopping before having every single layer dissolved. The only thing left of this both strict and poetic questioning was the word “I”, left on an empty stage. Max, I think “bathwater” somehow refrained from being consumed easily, even though the single elements of the performance have been clean and clear in their shape.

Max: Oh Lea, I think your shift from “clean” to the “act of cleaning” captures well what these performances did on several levels, specifically “bathwater”! Maybe similarly, I felt as if Jupiter Brown’s performance was clearly more invested in the process of cleaning than being clean. In the queer bathtub that Jupiter so generously made public to the audience, cleaning had nothing to do with the false dichotomy of clean bodies versus dirty bodies. On the contrary, cleaning here felt more like an act of exploring and caring for, an act of self-love both soapy and ordinary. How Jupiter looked around in the space: a moment of intimate recollection while at the same time seemingly cartographing the space! I can only say: Heart eyes emoji.

I think it’s interesting that many of the performances were cleaning in a literal as well as in a formal sense. There were so many soapy moments! By which I mean: soapy in the sense that I loved them (there goes the cover of *critical distance*).

In Pawel Swierzek’s performance Of Coal and Rainbow there was a whole spectrum of scenes that dealt with clean to these different degrees of abstraction. The work begins with him turning on his head lamp in the dark, spotting us with its light, staring at us. A reversal of the clean light situation of the traditional theatre space that indeed didn’t feel forced at all. While Pawel empties out buckets of coal, only to then hoard it again, behind him in a video projection we watch an older white man talking about his working biography – about a life in the coal mine. Specifically, he very vividly remembers the act of afterwork showering with his fellow miners: The coal, he says, would have got them so dirty, that there was simply no other way than to nakedly brush it off from each other. But no, he seemingly assures the interviewer, there was nothing gay about this. Then there is a clean cut – not for Pawel, who is slowly dragging himself up with – but in the video material that is shedding light on his beautiful and baroque black dress, where Tara’s voice is now entering the scene. She remains invisible, but provides us with visual material and an astonishing oral history of the drag scene in Polish Upper Silesia, where apparently all of this – the coal and the rainbow – is overlapping. She lets us know that you could clearly make out the miners in the crowd, were it the dark circles under their eyes that gave them away? Tara herself, we are informed, is sick at this moment – and to have her voice heard in this context, is a rare opportunity of her drag self going public.

Why am I re-narrating this almost word for word!? Because I think the juxtaposition of these accounts is just such a brilliant layering of visibilities. It shows how queerness does not necessarily, not always refer to a transparent practice. There are moments, in which some men can touch each other, scrub each other, and it's not seen as visibly queer. Other people have a bit of make-up in their faces and it's visibly queer to an extent, that they have to keep it a secret.

Lea: Then there is at least one more turning point: The moment where it becomes clear to us that the miner that is interviewed, is in fact his father! Now Pawel also begins to interact with the video on stage: He enacts a delayed dialogue, letting his legs dangle like a defiant child. The moment creates an incredible vulnerability and shows the gap between Pawel’s and his father’s realities and truths, opening up a space to think about generational and other forms of temporality. Somehow didactic it was also a touching and intimate piece of performance. I loved it!

Let’s move to the most soapy part of the evening: Ana Laura Lozza’s and Bárbara Hang’s immersive performance “consumation”. Finally a real piece of soap entered the stage accompanied by a huge plastic bowl filled with warm water and the audience was divided into two groups. Surrounded by the visitors sitting in a circle, the performers announced that we are going to use the one soap together for the following twenty minutes until its liquidation, until it is, as the title has it, consumed. At the beginning I thought: Okay, that’s easy to understand. You want us to perform some kind of cleaning ritual and create a community. But I have to admit that I was really surprised by the way the different visitors reacted. Some seemed to have exactly the same perception as I had but surprisingly many of the other participants took the performance as some kind of game with a challenge they wanted to win. The result was enjoyable: A woman scratching the soap with her nails, other participants washing their hands super slowly while seemingly trying to create consumable moments and views for the people watching. Only one time someone washed another's hands and created a private space in public for a minute or two. Watching the others trying to understand the “mission”, win the game or performing a ritual was contemplative for me. My thoughts started travelling and produced some kind of time shift for me. The twenty minutes passed nearly unnoticed.

For me as a visitor and observer of the performance’s first run arose the wish to also be part of the second presentation of “consumation”. What what was your experience, Max? Did you wash your hands? I have to confess that I only have watched…

Max: I did not wash my hands, Lea. I, too, only watched others do it: the ordinary participants performing ordinariness, and the professional performers – who of course happened to be among them and then put on a hand washing show of their own. Both of which seemed to me, as this personal person I am, sometimes more interesting and sometimes less. But I was overall surprised how a clean one idea performance can hold this bocquet of actions together, while at the same time not being an over-definitive framework. The kind of clean setting that “consumation” was inviting us into, both formally and performatively felt like a virtuosic style of vulnerability. This may seem too oddly specific, but I think you could even make out this specific style in the way Barbara and Ana Laura announced the performance and its rules: A tone that was such a unique combo of openness and determinacy.

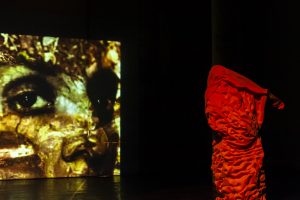

The evening began on a less participatory note, though: The Dispossession, a piece by Allison Wiltshire and Genevieve Giuffre, which felt to me – dare I say it – refreshingly theatrical!? In the beginning of these 20 minutes we witness a strange creature slowly beginning to move, to curl, to wriggle, until suddenly a head hatches from its pink hull. A head, that at first is not at all, but then at one point: merely human. Synchronized with this carefully choreographed transition in the background we see another shift happening: There are highly stylized object textures, against which very slowly a human face becomes visible. This face belongs to a body that is touching itself with varying amount of pressure, ranging from tender to fierce. Everything is stitched together neatly, MTV-era music video style. The performance then is shifting genre two more times: In a monologue we are told visceral tales of exploding pig skin and other anecdotes from the world of anti-ageing. In the end, there is then a futuristic catwalk situation that most prominently features my secret star of the night: a dental mouth spreader. I’ll also take a minute to put the German word here as well, because it’s so, so icky and in a very German way: Mundspreize. Eww.

In general, I think, I found it super interesting how The Dispossession was approaching its science fiction framework not in an overly dramatic way, as is often the case, but with a sense of humour as well. A lot of the aesthetic decisions were coming not only from the clean discourse of the beauty paradigm itself, but from dealing with the genre of science fiction. For me, it was in fact a certain ironic dissociation between the various stylistic devices that made this particular dystopia so special: The future doesn’t always look as clean as chrome. And sometimes a cleaning that is mapping, on the other hand, takes the form of wood texture close-ups as well, while a couple of fingers gently press a cheek.

Lea: Of all the nods to genre, The Dispossession especially reminded me of old horror movies and their use of stop motion technique. I think for example of the costume the performer was wearing in the first part of the performance – the strange pink cloth you briefly mentioned – combined with halting dance-like moves. The shade of pink made me think of a huge grotesque wrinkle lost somewhere on the way between fiction and reality, forgotten next to a trash can in a hospital for cosmetic surgery. After having been born, after having left the pink fleshy fabric, the performance kept its artificial undertone: Weirdly hyped about something the performer quoted fashion and instagram poses as the room suddenly turned from dark into blinding bright light. Overstraining us as an audience in a playful way we became eye witnesses of the power of beauty industries creating modern myths. Impressive how Wiltshire and Giuffre never started to teach but dissected and distributed their subject linking it with several mediums such as choreography, language, sound, video and voice-over. And alway with a wink and the courage to use a harsh break!

I was excited about how political the second edition of Dirty Debüt was. I think it was not least the fundamental ambivalence of the evening – dealing with clean framed by the permission to show something dirty – that created a space for that. For me, within this framework the artists shared interesting perspectives on how a struggle against the conventions of body politics might be entangled with a struggle against conventions of the artistic field. It become clear that for the creation of new aesthetics – that want more than just to mistake mocking neoliberalism for critique – it’s necessary to leave more room to experiments and discussions. Also to just appreciate ideas as such, while on the other hand reconfiguring the concept of the clean and consumable artwork.

Max: After all, clean might just be both the cleaning and getting dirty we did along the way! Plus the friends we made! Thank you, Lea, for talking to me!